|

|

||

|

|

|||

|

Summer IN RETROSPECT 2010

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

STUART K. CASSELL: Tech's gutsy go-to guy

|

According to Bennet Cassell (dairy science '68, dairy cattle genetics M.S. '72), a recently retired Tech professor of dairy science and Stuart's nephew, his uncle "had a vision of Virginia Tech as bigger than an agricultural and engineering school." Stuart worked hard to realize that vision, but turning it into reality was not easy. "The university was more under the oversight of the state government then, and Stuart spent a lot of his time figuring out how to get things done," says Ray Smoot, university treasurer and COO of the Virginia Tech Foundation, who worked for Cassell and succeeded him as secretary-treasurer of the foundation, another of Cassell's creations. Sometimes, that "figuring out" involved superior gamesmanship. For instance, Cassell wanted a golf course on campus, but the governor believed that investing in one would waste taxpayers' money. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Undaunted, Cassell had nine turf-grass test plots constructed that were then connected by stretches of grass resembling fairways. When the governor objected to the use of state funds for a golf facility, Cassell reportedly said, "Governor, show me in our books where VPI spent any money on a golf course." Perhaps being one of 12 children taught Cassell how to work his way through obstacles to reach goals. Born in 1910, he grew up on a farm near Rural Retreat, Va. His father, Sidney "S.S." Cassell, was a farmer and teacher who encouraged his children to go to college. Some attended colleges in Salem, Va.; five went to VPI, including Stuart, who enrolled in animal husbandry in 1928. In college, Cassell was active in agricultural organizations; in sports, an interest he maintained throughout his life; and in the corps of cadets, where he attained the rank of lieutenant. But he also found time for tomfoolery, joining several other upperclassmen in taking the laundry bags of some freshmen to fill with apples from the college orchard. When school officials discovered the would-be thieves in the act, writes Harry Temple in The Bugle's Echo, the cadets fled, abandoning the bags.

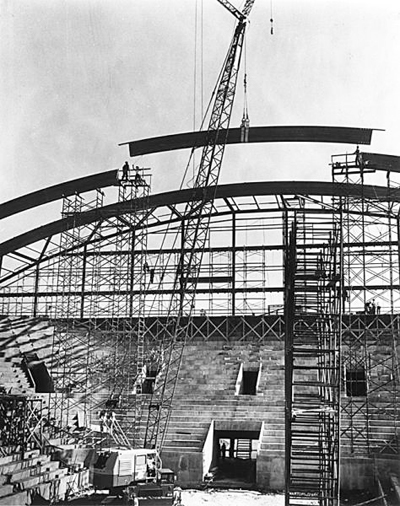

In 1939, he accepted a position as director of the Agricultural Adjustment Administration in Virginia. Cassell turned his program, which regulated the sale of farm commodities at pre-set prices, into a model for the country. In 1945, he received a lucrative job offer from the Federal Land Bank in Washington, D.C., but it was trumped by one from John R. Hutcheson, who was acting VPI president. Hutcheson offered him a position as financial and business manager, effective March 1, 1945. "When I took the position," Cassell later said, "it seemed as if I got the duties no one else wanted to do." He quickly turned his job into one of power, prestige, and persuasion, working seven days a week and earning the confidence of presidents John R. Hutcheson, Walter S. Newman, T. Marshall Hahn Jr., and William E. Lavery, all of whom valued his vision and relied on his ability to get things done. As an example of his quickly acquired standing in the college, when Hutcheson was hospitalized in late 1946, Cassell and Newman, then the vice president, shared the presidential duties. Cassell was a complex man, as evidenced by the litany of adjectives used to describe him: soft-spoken but direct, caring, gentle, gruff, authoritarian, compassionate, dedicated, effective, brusque, persistent, hard-nosed, loyal, dependable, and even sneaky. Lavery called him "a man of great strength, integrity, and vision." Those traits and his work ethic--"If you want to get ahead, you have to work a little harder than anybody else," he once said--ensured his success. His willingness to bend the rules also played a significant part. "He knew," Smoot says, "how to get things done," a trait that led Hahn to call him a "giant of the university" and Lavery to see him as "larger than life." Cassell met challenges head-on. Faced with the need to house an influx of veterans at the end of World War II, he set up temporary lodging in war-surplus buildings at nearby Radford Arsenal and filled three locations on campus with trailers. Veterans dubbed one of the trailer parks, located in the vicinity of today's Cassell Coliseum, "Cassell Heights." During his latter 31 years of employment at VPI, enrollment grew from 738 to 17,740, and he was involved in the construction of 36 major buildings and the renovation of another 15. He played a key role in raising money to construct the War Memorial Chapel and today's Alumni Mall, which involved the destruction of numerous large trees. Facing strong opposition from students and townspeople, Cassell ordered a contractor to begin cutting the trees one day at 6 a.m. By 8 a.m., they were down. "You never saw such fussing and fuming, but there wasn't anything they could do about it then," he later said. When he and Hahn orchestrated the rise of the athletic program, Cassell developed the physical plant, which included Lane Stadium and the coliseum. "Stuart concocted the idea to build a coliseum and to get it funded as a student activity center so the state would put up the money," Smoot recalls. Cassell wanted a 10,000-seat arena, but the state would only approve 8,000 seats. "The reason the seats are so small," Smoot notes, "is because Stuart put 10,000 in a space designed for 8,000." Cassell died unexpectedly on Oct. 6, 1976. A month later, the board of visitors passed a resolution renaming University Coliseum the Stuart K. Cassell Coliseum to recognize his role in making the facility a reality and to express the university's "deep appreciation and gratitude for his untiring work, outstanding leadership, and unfailing good humor." Cassell devoted his worklife to his vision of the modern university and, in the process, affected the physical growth of Virginia Tech more than any of the four presidents he served. Today's campus stands as mute testimony to the efficacy of that vision--and his unrelenting drive to make it a reality. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||